By Rick Love with Katie Moller (Reprinted from the rogue art history website Sartle with permission)

‘We came here to praise traditional art history survey textbooks, not to bury them.’

We love Gardner’s ‘Art Through the Ages’, Janson’s ‘History of Western Art, and Laurie Schneider Adams’ ‘A History of Western Art’. They are immortal classics, and we relish the many hours we have spent reading them and teaching from them. Gardner broke new ground by incorporating non-European art, and Janson’s herculean effort to physically visit as much of the significant art of the western world as humanly possible took many decades. Gardner’s oeuvre was first published in 1926 and was the most widely used art history textbook, until Janson finally published his seminal work in the 1980’s. Janson’s book became a bestseller even outside the world of art history pedagogy. Adams changed the layout and the flow of art history by shaking up the presentation from linear to topic based. However, from the perspective of a present day art history teacher or student, these works have all of the same drawbacks of paper textbooks on other subject matters, as they are:

- expensive,

- heavy,

- cannot be searched electronically,

- are not interactive

- are not widely available, especially in emerging markets where the majority of the world’s population lives, and

- are updated infrequently, and those updates require students to purchase or borrow the new edition, while the obsolete older editions end up in the trash.

This last point has extra meaning when it comes to the study of art history. Art history is more subjective than engineering, biology, or math. While there is little disagreement among art historians on many topics such as how specific mediums and techniques developed, or how particular schools or movements evolved, the choice of which artists and which art to highlight is often not objective. And as history is written by the dominant actors in it, so is art history, with the predictable result that most art history has been written by white male art historians. They have generally been biased in favor of art produced by white male artists, and have studied and documented that art from a white male perspective, thereby depriving us of a deeper and richer understanding of the topic. When women artists are mentioned they are often talked about primarily in the context of their connection to significant male artists, furthering the myth of male primacy in art. For examples of this see Judith Leyster/Frans Hals, Camille Claudel/Auguste Rodin, Georgia O’Keeffe/Alfred Stieglitz, Frida Kahlo/Diego Rivera, and Helen Frankenthaler/Robert Motherwell.

Fortunately, digital art history resources not only outshine traditional textbooks in that they are cheaper, do not require upper body strength to transport, and are easily searchable and interactive, but they can be, and usually are, updated in real time. This last feature allows art historians, in theory, to now incorporate content on art and artists from all genders and ethnicities quickly. The limitations of traditional printing and editorial choices do not apply in our digital age. For our essay below, we examined the diversity of the universe of artists covered in three leading traditional art history textbooks, as well as the diversity of artists covered by the online digital art history resource we know best – Sartle. The results speak for themselves, but we will highlight a few key points below.

Summary of Most Recent Textbook Editions

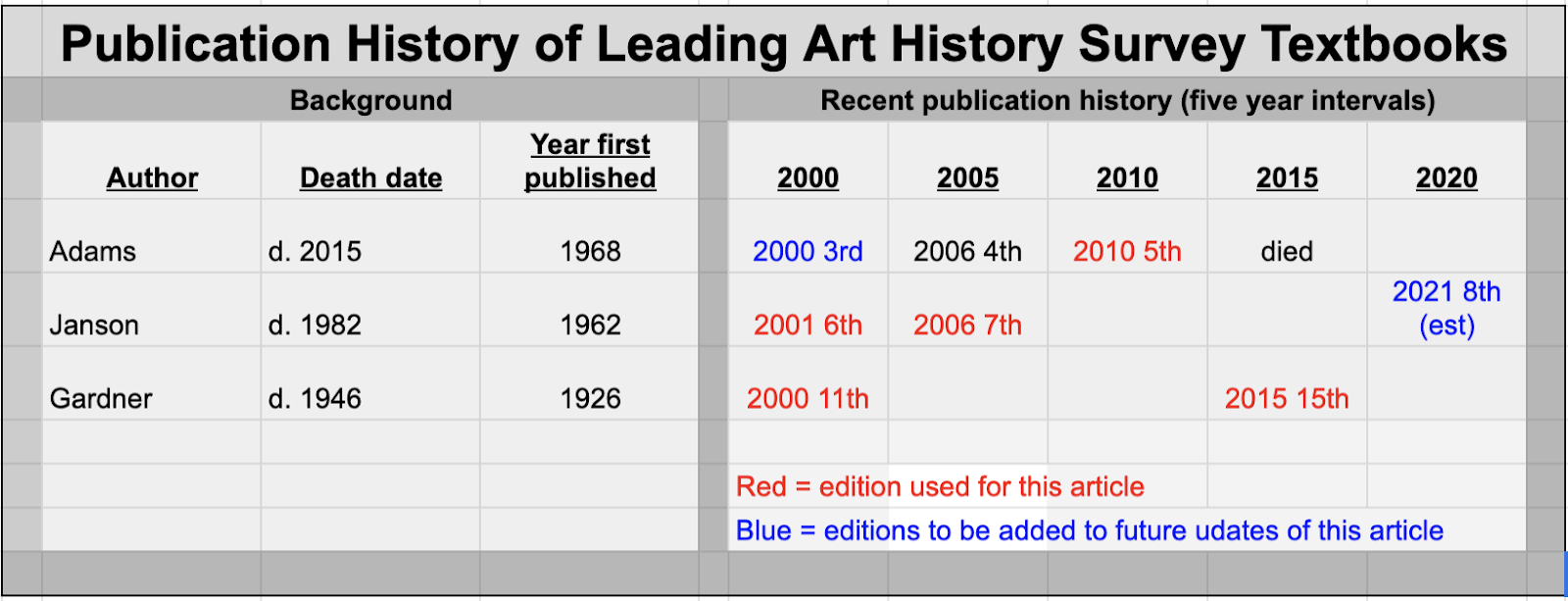

For this article, we reviewed two recent editions of the Gardner and Janson survey textbooks, and one edition of the Adams textbook. In a future update to this article, we will add the third edition of the Adams textbook (in order to quantify changes between the third and fifth editions), as well as the upcoming eighth edition of the Janson textbook, which is expected to be released in the summer of 2021. The following table summarizes the examined, and to be examined, editions:

Gardner’s ‘Art Through the Ages’

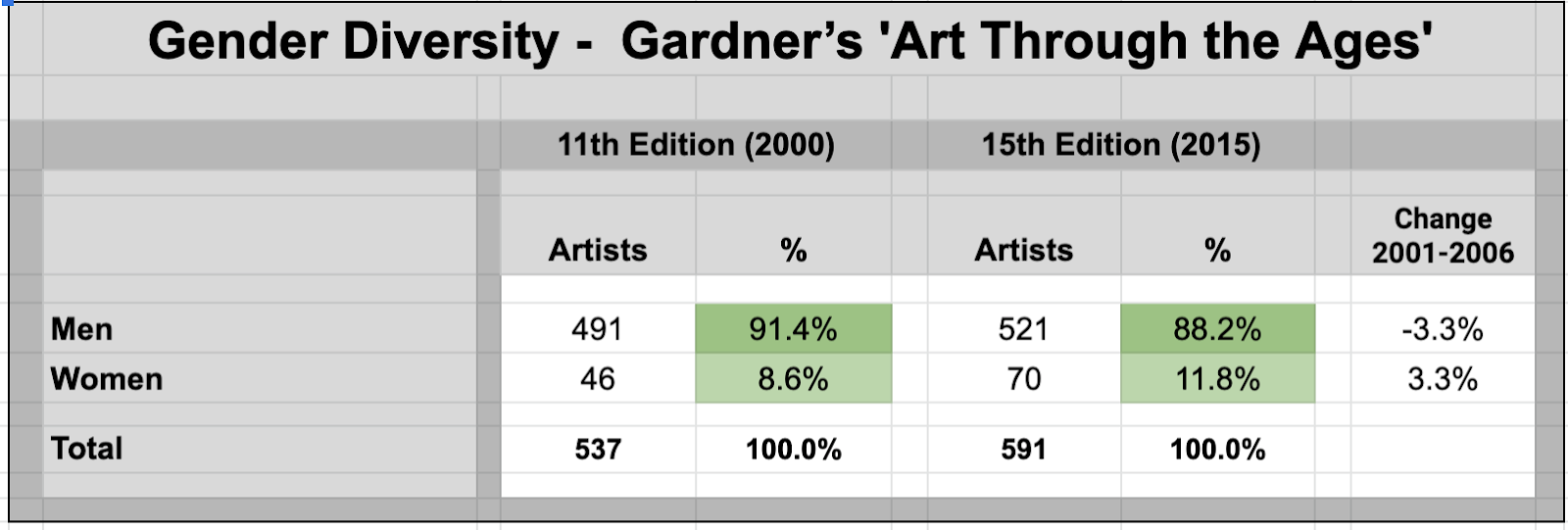

As can be seen from the table below, in spite of Helen Gardner being female herself, the artists featured in Gardner’s ‘Art Through the Ages’ are overwhelmingly male:

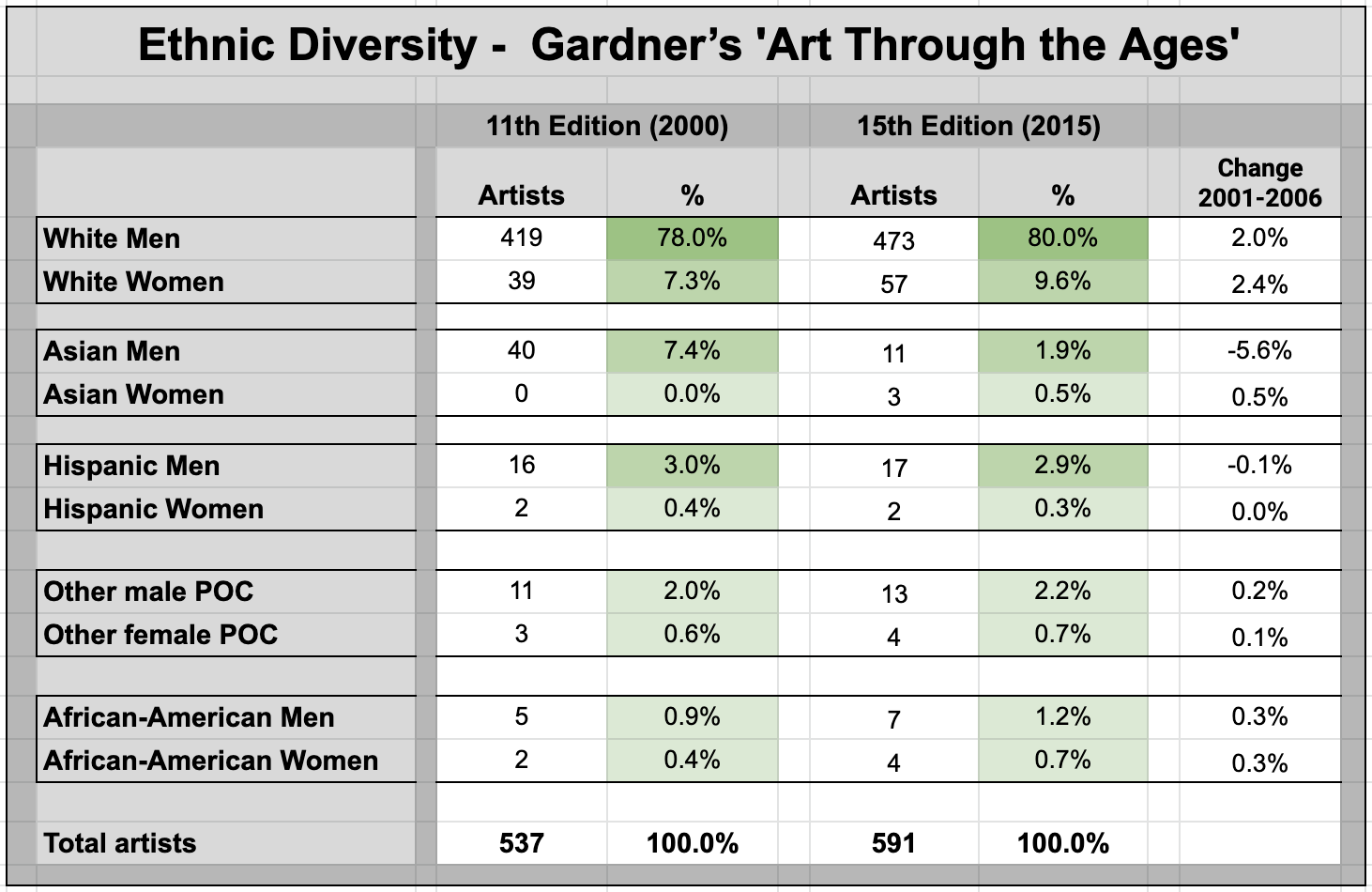

On the ethnic diversity front, Gardner has zero Asian female artists, and yet Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, and Ruth Asawa all occupied significant positions in the canon of modern art history well before her 11th edition was released.

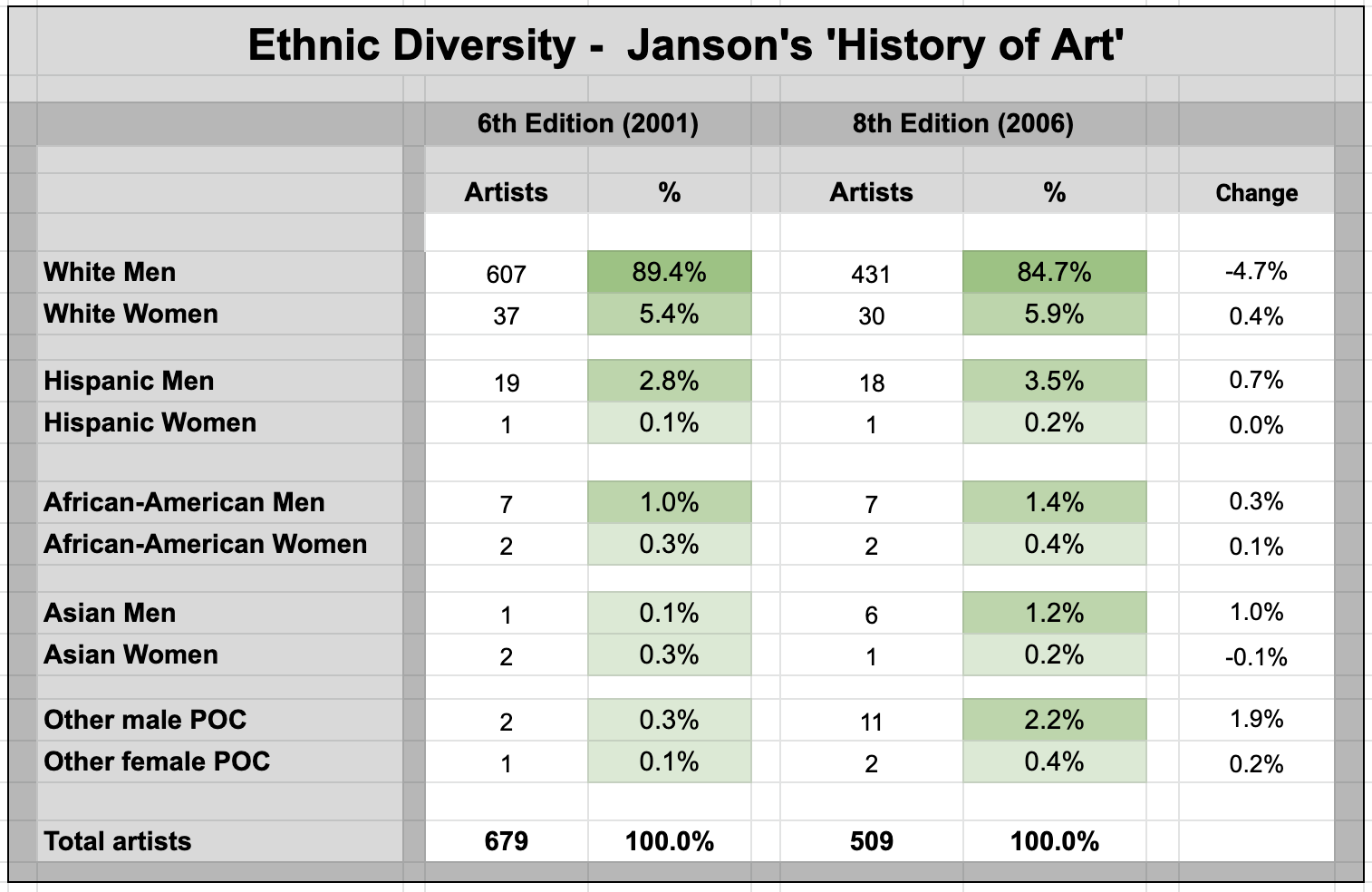

Janson’s ‘History of Art’

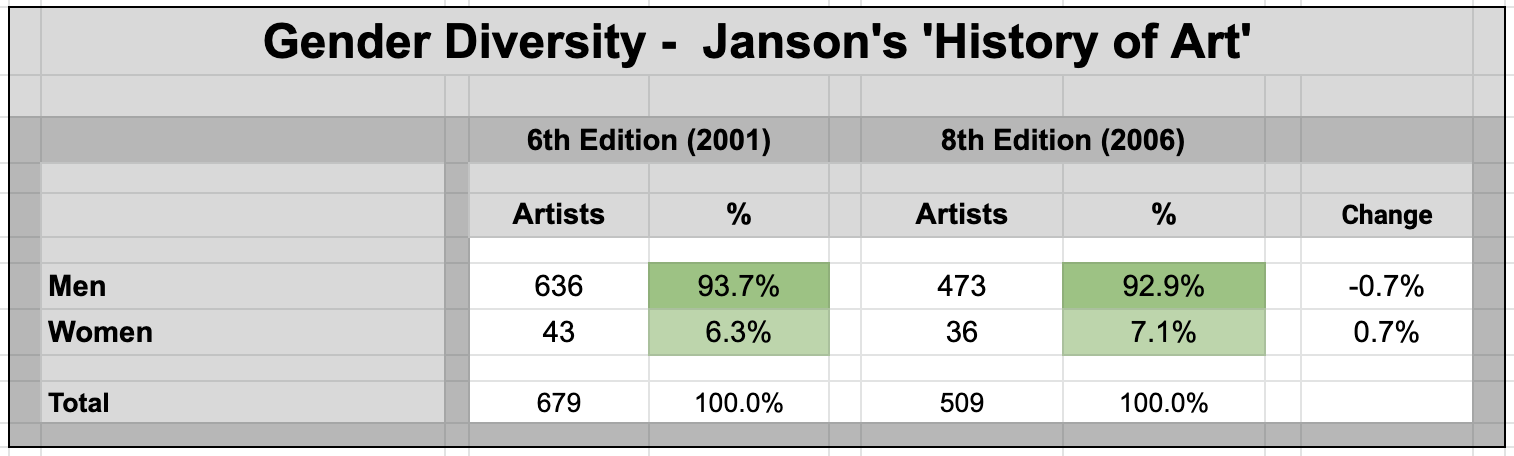

Only 7.1% of the artists featured in Janson’s 8th and most recent edition are female, which seems low, even if we take into account the fact that for much of history women were not permitted to make art. Nonetheless, 7.1% was an improvement over the 6th edition, which was published five years prior, where this figure was only 6.3%. So the absolute percentage is low, and the change in it over time has been glacial.

Likewise, less than 10% of the artists in the most recent edition are non-white, although that is a doubling from the 6th edition, which had this figure at only 5%.

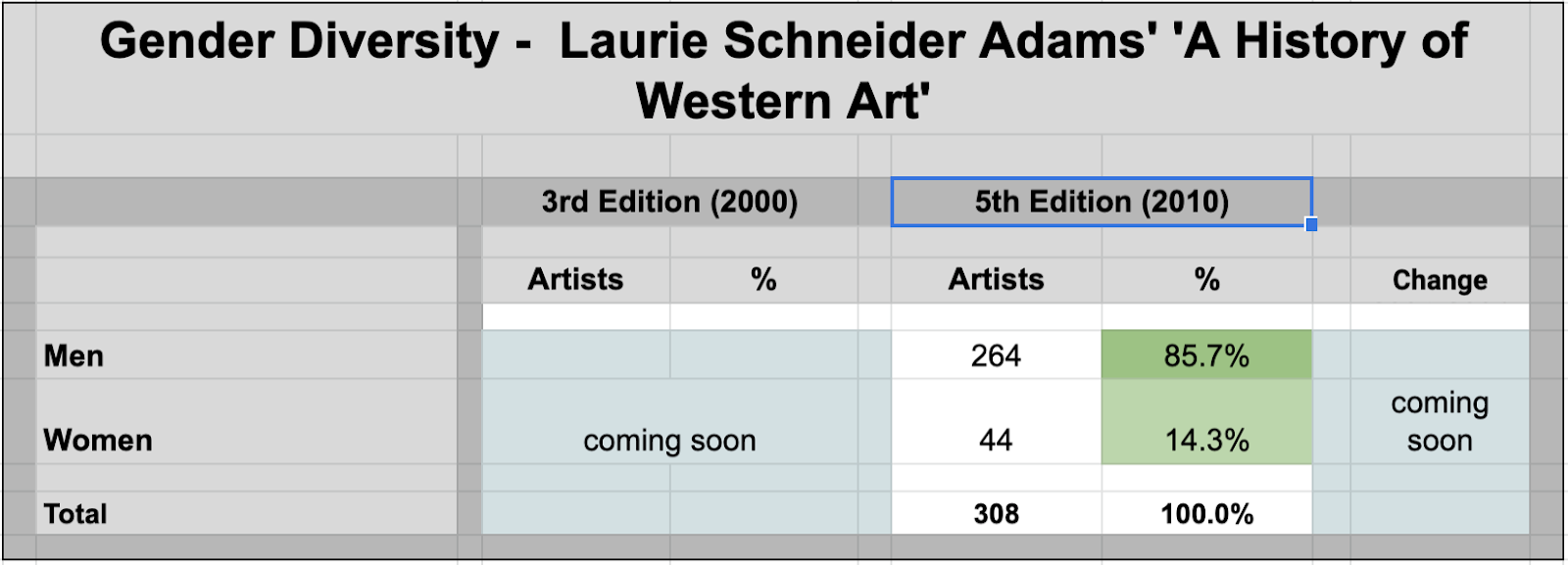

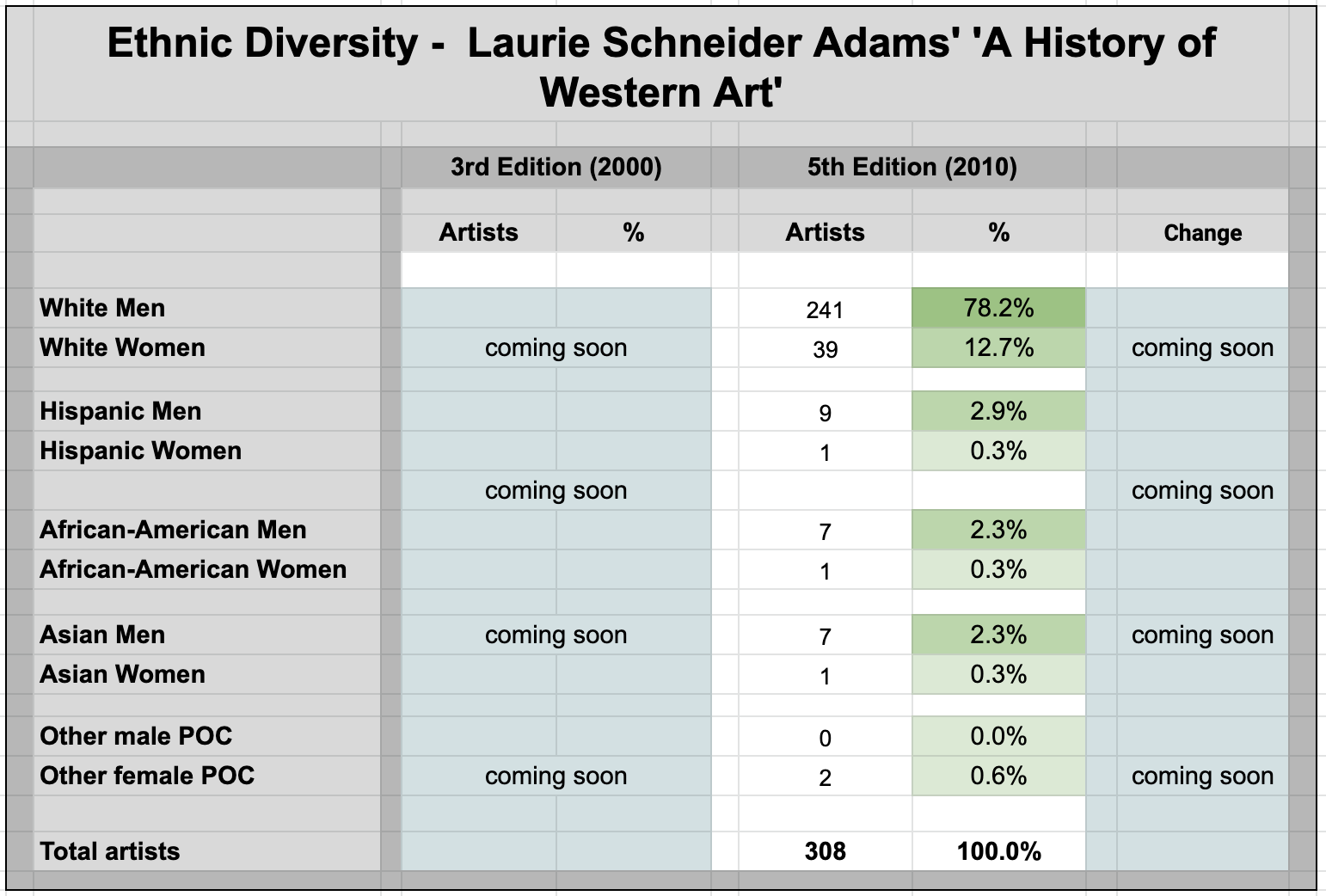

Laurie Schneider Adams’ ‘A History of Western Art’

Laurie Schneider Adams’ text is a more recent arrival than Janson or Gardner. Her text and layout are a bit more digestible and user-friendly than the earlier editions of Janson or Gardner, which is why her book took off and many art history professors still use it in their classes. That being said, she features fewer artists than Gardner or Janson.

As of this writing, we only have data on the latest edition of her book but we are analyzing the 3rd edition, and will update our table below shortly. As a female author of a widely used survey textbook, it is interesting to note that she does feature more female artists. Female artists make up a double digit percentage of total artists featured in her text, but as we shall see below, that percentage still falls below where digital resources such as Sartle are today.

Things are a bit more disappointing when it comes to the ethnic diversity of the artists featured in the Adams text. Just like Janson and Gardner, the split between white artists and artists of color is about 90/10. Is this because publishers of traditional textbooks can’t bring themselves to change the model? Or is it because the faculty teaching these classes have bought into the traditional art history paradigm, and it is hard for them to give up that worldview?

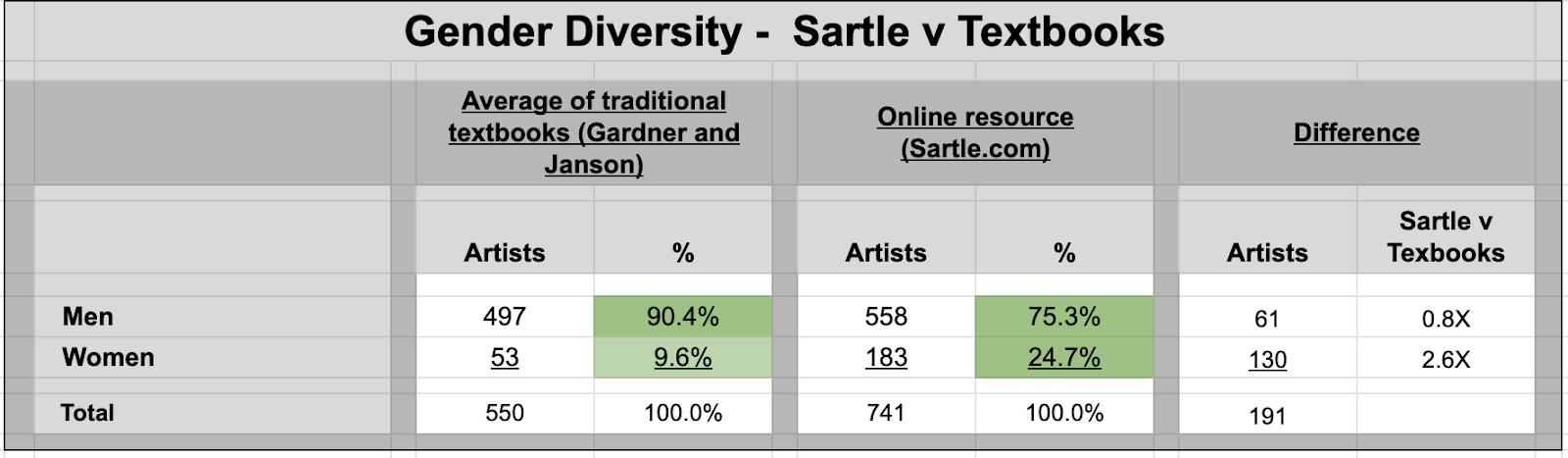

Traditional Textbooks vs. a Representative Digital Resource (Sartle)

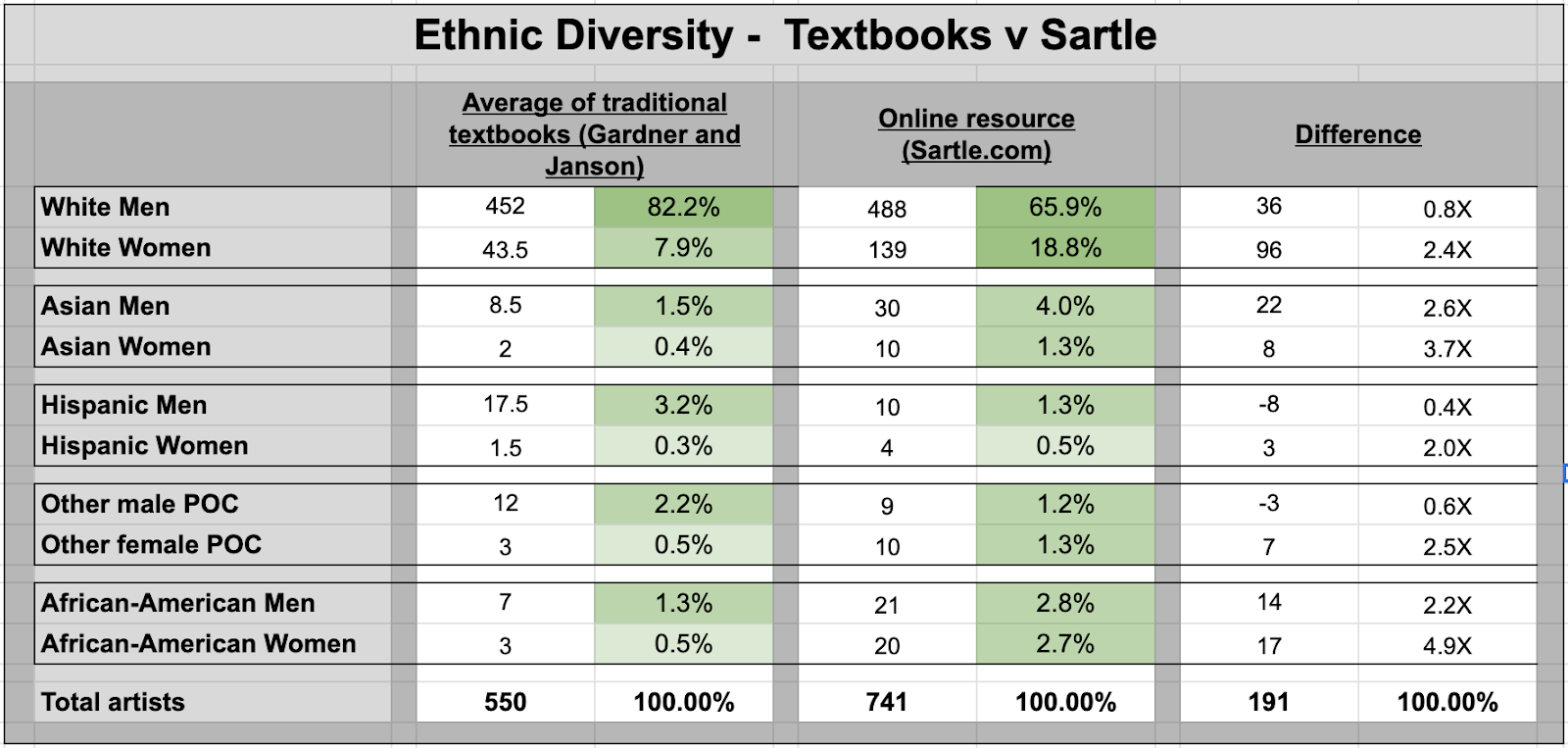

First of all, our representative digital art history resource (Sartle) covers 35% more artists than the latest editions of the textbooks do (741 versus 550).

Furthermore, the percentage of artists who are women is more than double that of the textbooks.

Finally, the artists featured in Sartle are also over 50% more ethnically diverse, with over 15% of them non-white, versus less than 10% for the three traditional textbooks.

Conclusion

Because they can be updated in real time, digital art history resources can be more nimble than textbooks, and more able to more quickly reflect the now generally accepted view among art historians that art history was not shaped exclusively by white male artists. The disparity between the gender and ethnic diversity of artists found on Sartle versus the textbooks proves that this is in fact the case. In addition to featuring more gender and ethnically diverse artists by a wide margin, the few areas where the textbooks show a greater diversity of artists (Native American and Hispanic men) are being worked on by the Sartle staff, who expect a remedy within months, not years. Of course, as indicated above, digital resources also beat traditional textbooks in ways beyond the fact that they are way more nimble and flexible when it comes to adjusting content in real time. We address these other ways in our upcoming article, ‘Digital Resources Disrupt Art History: New Perspectives on Art by Gender and Ethnically Diverse Artists. How modern online tools and resources are beating traditional textbooks,’in which we examine the leading dozen digital art history resources and rank and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses.